Starting the search in Ghana

When this blog is published, Annemieke and I have arrived in Ghana and are on our way to Elmina, the place Presto departed from on his voyage to the Netherlands in the 1740s. We made the trip in reverse, but in a stunted manner. We did not travel by ship, arriving first at Axim in the west of Ghana, and then sailing on to Elmina, to anchor in the roadstead and be ferried ashore on a small boat or canoe. We arrived by plane at Kotoka International Airport Accra, spent the night in a comfortable hotel, and now travel to Elmina in an equally comfortable rental car.

And equally so, when we arrive in Elmina, this will be a very different place from the one Presto left some 270 years ago. One of the most important tasks therefore is for us to recreate the world Presto came from. In this last blog written from Europe, we once more revisit the clues and hints Christiaan left for us in his later life, as a starting point for the historical recreation of his world in the following blogs, which we will write from Ghana.

Clues on origin and arrival

Throughout his life, Christiaan left hints about his African origins and arrival in the Netherlands. That this is helpful for his identification has been shown in the earlier blogs. The letters Christiaan wrote to the King from 1815 onwards, and the letter his daughter Antje wrote in 1830 are most helpful here.

In all his letters to the King Christiaan wrote that he was born on the

Coast of Guinea ('de kust van Guinea'), by way of introduction, and rather than emphasising his colour or former name of Presto. But he does not give many more details.

In her

letter to the King, asking for assistance, his daughter Antje gave some additional information. She wrote:

'That in his lifetime, her [...] Grandfather was General on the Coast of Guinea, where her father was stolen as a child by the Guineans'

This is a very valuable clue. We may expect that this story came from

her father. And the element of the 'grandfather-general' is new. Who can

this 'General' be? The governor-in-chief of the Dutch Gold Coast had

the official title of 'director general.' In daily practice this was

often shortened to 'general,' in which form it even entered into

official documents. When we then look at the period in which Presto came

to the Netherlands, this coincided with the term of office of Jacob

Baron de Petersen as director-general over the Dutch Gold Coast. He

arrived in 1740, and left in 1747.

But obviously, General Jacob de Petersen was not the biological father of Presto. So talking about him as 'grandfather' must be understood in a metaphorical or figurative sense. Apparently Christiaan had spoken to his family about De Petersen having been a fatherly figure to him. Possibly even making De Petersen his only connection to Africa.

In the

last blog we showed how Jacob de Petersen was involved in the transfer of two young boys in Elmina in 1744. We here asked the question if these could be Presto and Fortuin. In view of Antje's statement, this suggestion becomes more plausible.

|

| Jacob de Petersen registered on audience with Prince Willem V of Orange Nassau, 7 March 1771. Coll. Koninklijke Bibliotheek Den Haag |

Besides, De Petersen was in a position to bring children with him to the Netherlands. He was a very powerful person in the West India Company, and very wealthy as well. He had served the W.I.C. from 1725 onwards in executive positions, first in Curaçao and afterwards in West Africa. His relationships with the upper classes of Amsterdam and the Hague were strong, and he had

a good relationship with the Court of Orange-Nassau as well. After his final return to the Netherlands in 1747 he first became a W.I.C. director, then the presiding director, and finally the representative of the Prince-Stadtholder Willem V in his capacity of governor-general of the W.I.C. By then De Petersen was the most powerful and influential figure in the running of the Dutch Atlantic slave trade and the Dutch West Indian colonies.

When Jacob de Petersen requested his dismissal as director-general of the Gold Coast in 1746, he had a clear idea about the remainder of his career. For starters he set up a private slave trading expedition. He hired the private slave trading ship Watervliet and prepared for a slave voyage that was to transport more than 700 enslaved men and women to Suriname. He travelled on the ship himself.

The fortunes of the voyage are currently a matter of academic research.

The records show that in Paramaribo, Suriname, Jacob de Petersen

changed ships and boarded the ship Jalousie, with his servants. It is

very well possible that Presto and Fortuin travelled with Jacob de

Petersen to the Netherlands in 1747, together with a richly adorned

hammock, as present for the Princess Carolina.

Jacob de Petersen's Gold Coast

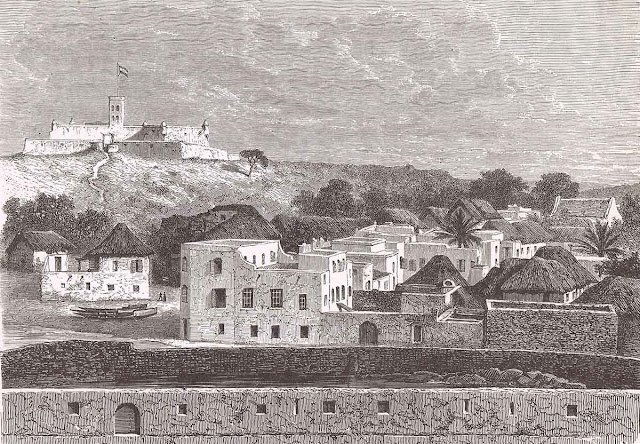

So now we know where to start: on Jacob de Petersen's Gold Coast. To recreate Presto's early years and experience in Ghana, we have to look for the Dutch Gold Coast as it was in Jacob de Petersen's time, the period between 1740 and 1747. Who was there, what did it look like, what activities were going on? And: how do you make such a reconstruction in an environment that has changed beyond recognition?

In the oncoming blogs we will address these questions. However, we cannot solve them alone, and all contributions from our virtual fellow travellers and followers are welcome. What do you think about Presto's early years?